Katrina and New Orleans stand as iconic names in the history of hurricane storm surge flooding in the U.S., but recent storms named Sandy, Ike, Hugo, Isabel, Irma, Harvey and Andrew have highlighted the vulnerability of coastal cities all up and down the East Coast as well as in the Gulf of Mexico.

Both the intensity and frequency of major hurricanes are likely to increase as the energy in the climate system is enhanced by warming due to greenhouse gases. Added to the inevitable rise in sea levels as the oceans warm in response, planning and preparing for flooding would seem to be a high priority for all low-lying cities.

The previous essay in this series described the major infrastructure projects constructed in four European cities to resist both recurring historic storm surges and accepted rising sea levels. As climate change stories in the U.S. media seem to concentrate on real-time disaster reporting and the politics involved, I had assumed that most U.S. cities were not planning for the rising tides.

That assumption turned out to be incorrect. Building on the tragedies wrought by those named storms and others, recognition of the threat can be found in planning documents for nearly every major coastal U.S. city. At their best, these represent the work of dedicated planning professionals, engaged citizen groups and local leaders to construct plans and begin projects. How far planning and projects have progressed, however, varies widely.

Financial commitments vary as well, as we will see, and while economics is not the focus of this Substack site, numbers are, and here are a few that might provide context for what follows. If the United States spent as much on a per-citizen basis as the Dutch on holding back rising seas, that would come to about $30 billion annually. A GAO report building on data from NOAA estimated the cost of damage from four recent named storms as $170 billion for Katrina, $74 billion for Sandy, $131 billion for Harvey, and $52 billion for Irma.

Preparedness might be expensive, but so is disaster recovery.

So, Let’s start with a list of cities most likely to suffer from sea level rise and then survey quickly what has been done for each. In general, projects can categorized as “hard” (resistance), involving sea walls, gates and pumps, or “soft” (resilience), emphasizing incremental changes in infrastructure and water management.

Resistance is generally more expensive up front, and projects take longer to complete, but also provides a long-term solution. Resilience is incremental and adaptive, but requires continuing support. All of the projects described in that previous essay on St. Petersburg, Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Venice were “hard” solutions.

Often included in the adaptive, resilience approach are concepts from the Dutch “Room for the River” project which, as the name implies, creates spaces that can be flooded temporarily, such as parks and wetlands, without major damage. Not all flooding need be prevented; some can be accommodated.

And the valuable experience gained by the Dutch has also impacted U.S. planning through what are called The Dutch Dialogues. Led by a private consulting and engineering firm working in conjunction with Dutch experts, this solution framework hosts a series of meetings involving local leaders and concerned citizens in a multi-day to year-long discussion of science, threats and possible solutions. Some of the cities described here have employed this process.

In terms of technologies that let us see our future, NOAA supports an interactive site based on a digital elevation model (computerized elevation map) of the U.S. The site allows users to generate maps of expected flooding impacts for different increases in sea level. This map for Southern Florida is for a 3 foot rise, a likely scenario for 2100 described in the most recent IPCC science report.

Some of the cities frequently cited as most threatened by sea level rise as a result of these kinds of analyses include New Orleans, Miami, Houston, New York, Charleston, Boston, and Norfolk/Hampton/Newport News, VA.

We will look very briefly at each of these, but begin with a set of lesser-known and older projects, and rather than go from biggest project to smallest, this tour will go north to south, starting in New England and ending in New Orleans. In this essay format, this rapid tour will read something like an annotated bibliography. References to each location and project are cited in the Sources section at the end.

New England

To begin our tour, I was surprised to learn that several cities in my home region of New England completed projects decades ago to protect harbors and cities from storm surges, driven in part by historical events like the iconic Hurricane of 1938.

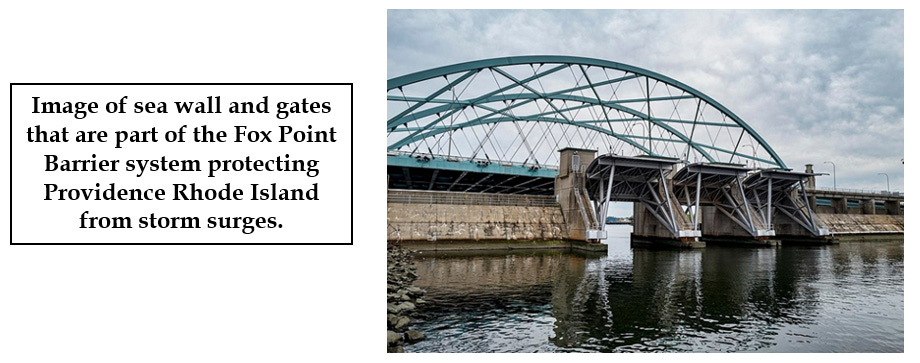

Three projects were completed in the 1960s to protect the harbors of New Bedford, MA, Providence, RI and Stamford CT. They are all “hard” solutions consisting of seawalls and barriers with mechanically controlled gates that can be closed when storm surges threaten. These systems have been credited with saving millions of dollars in storm damage. Their initial costs ranged from $14 to $18 million, about $120 to $160 million in today’s dollars.

Boston and the state of Massachusetts have developed tools for mapping the possible extent of flooding with sea level rise. Faced with a $30 billion price tag and a decades-long time frame for taking the hard, seawall approach, Boston has instead opted for a softer incremental strategy based on integrated plans for four neighborhoods. The plan includes what is called the Climate Resilient Design Standards and Guidelines for Protection of Public Rights-of-Way.

The first project currently underway focuses on Boston Harbor and the North End, is projected to cost $15.3 million and relies on elevating infrastructure and identifying low-lying recreational fields and other areas that can accommodate water overflow. The city has committed to spending $20 million per year, or 10% of its annual capital spending, to move the resilience plan forward. Public statements, plans, and budgets all express a sense of urgency about sea level rise and climate change in general.

New York City

Hurricane Sandy in 2012 emphasized the current vulnerability of infrastructure as well as commercial and residential structures to major storms even at current sea levels. A proposal for a major seawall and gate installation at the entrance to the harbor, similar to those in Holland and developed in collaboration with Dutch experts, was estimated to take 25 years and cost $119 billion. That approach, projected to protect the city for 100-150 years, has been rejected

Instead, there are a series of local and incremental projects underway and planned, including:

· The Eastside Coastal Resiliency Project - $1.45 Billion, to be completed by 2025.

· A plan to protect lower Manhattan - $5 Billion, currently unfunded

· A Living Breakwaters Project on Staten Island - $107 million

· A 5.3 mile long seawall on Staten Island - $615 million

· The Metropolitan Transit Authority resilience project - $7.7 billion

Migration is also part of the plan. A statewide office has managed the purchase and demolition of hundreds of low-lying homes in Oakwood Beach, Graham Beach and Ocean Breeze on Staten Island.

Norfolk/Hampton/Newport News

Active participation in the Dutch Dialogues in 2015 changed the direction of the sea level rise discussion in Norfolk. The change was summarized by one of the participants as a shift from resistance to resilience. The initial proposal for a hard seawall has been replaced with a $112 million project funded by a Housing and Urban Development grant to protect two neighborhoods. The project will use a tidal gate, raised roads and improved stormwater capacity, but also includes a resilience park with a berm, a restored tidal creek and wetland, and sports fields, a picnic grove and a "water walk" along a tidal creek. Other strategies for temporary water storage include an expanded creek and permeable pavers to filter runoff and reduce street flooding.

The project has been greatly expanded beyond this initial project. Recent infrastructure funding from the federal government has increased the scope of the project while maintaining some of the resiliency characteristics. Total funding is now about $615 Million

Charleston

A first plan produced by this historic city in 2015 emphasized improvements in drainage in response to increased flooding, predicted to increase from 2 major events per year in 1970 to as many as 180 per year by 2040. $235 million was set aside for the work.

In 2018-19, the city engaged in a year-long Dutch Dialogues process and developed a final report presented in 2020. Among its specific recommendations are to rebuild and raise the existing Lower Battery Seawall protecting downtown, something that had already been planned, raising a street on a seawall in the medical district, and improved management of stormwater.

Not included in the recommendations was support for an Army Corp of Engineers proposal for a $1.4 billion, 12-foot high seawall surrounding most of the peninsula on which the city sits. Charleston’s part of the price would be about $385 million.

In 2019-20 the city updated its 2015 plan in response to the Dialogues. The emphasis on the Lower Battery Seawall and improved drainage systems reflect earlier approaches, but at least a nod is given to minimizing future development in floodplain zones. The overall plan is said to provide protection for the next 50 years at a cost of $154 million.

Migration of a sort is gaining traction in Charleston: raising building by lifting them onto enhanced foundations. Strict historical preservation guidelines ruled out this approach initially, but lacking any other solution, a total of 46 houses have been approved for raising, at a cost of about $100,000 per structure. The city’s mayor suggests that hundreds more will need to be raised over the next 50 years. Some federal subsidies are said to be available. For example, FEMA announced in March that it would spend $8.4 million to elevate 31 homes in New Orleans.

Miami

Given its immense sea frontage, very low elevation profile, and concentration of high-value property right at the beach, Miami is often considered the U.S. city most vulnerable to sea level rise. The image at the top of this essay is from a NOAA projection. Here is another focused on the Everglades from the National Parks Conservation Association.

One source suggests 800,000 residents of Miami-Dade County could be permanently displaced by sea level rise. Another suggests that current waste water treatment plants could be relegated to isolated islands. A third presents maps showing that most of Miami roads are already in the 100 year flood zone. A recent NOAA study predicts all Miami streets will flood every year by 2070.

Miami and Dade County produced a report in 2021 highlighting the potential damage, but stressing adaptation and attempts to keep the Miami area livable. The Sea Level Rise Strategy describes five adaptation approaches:

Build on Fill: raise the land on artificial fill

Build like the Keys: elevate structures on pilings and live with more water

Build on High Ground Around Transit: promote new development in the least flood-prone areas along transit corridors.

Expand Greenways and Blueways: expand waterfront parks and make room for canals in the most flood-prone neighborhoods.

Create Green and Blue Neighborhoods: create a network of small spaces for water in yards, streets, and parks.

A considerable amount of mostly federal money is going into efforts not highlighted in this report. The first annual report on progress relating to this plan included $138 million in federal funds for beach replenishment, a recurring issue on eroding and sinking shorelines. The next big item was a $100 million award to match Army Corp of Engineering protection projects. Other much smaller items included land purchases, resilience for low income housing and watershed management and drainage.

Houston

In 2008, hurricane Ike demonstrated dramatically the vulnerability of the Houston/Galveston area to storm damage. Winds up to 110 miles per hour drove floods that destroyed 3,600 homes and led to 15 deaths.

In response to this and predicted sea level rise, the Texas Land Office and the Army Corp of Engineers have developed and proposed a now $29 billion dollar project involving several hard and soft components under the rubric of Multiple Lines of Defense. A hard seawall and ring levee would surround the city of Galveston. A series of four different storm surge gates would seal the entrance to Galveston Bay when needed. Dunes would be raised and ecosystems restored on the Bolivar Peninsula, and habitat restoration and raising of buildings would occur in Houston.

The planning and presentation process has featured a number of public hearings with detailed descriptions of the proposal. The plan has changed in response to public input. While there are doubts that this plan will meet the sea level challenge by the end of the century, the 2021 version of the proposal now sits with the Army Corp and awaits funding.

New Orleans

The history of floods and efforts to contain them is far too long and deep to capture here. Two well-reviewed books are noted in the Sources section below.

FEMA considers New Orleans to be the city most vulnerable to hurricanes. Flooding from tropical storms has occurred in 1909, 1915, 1947, 1956, 1965, 1998, 2005, 2008 and 2020. Two storms struck in 2005, including the most damaging – Katrina – which overwhelmed existing levee systems and flooded 80% of the city. I recall seeing an interview with a Dutch hydrologist in New Orleans right after Katrina who was visibly moved by the destruction, and said clearly that the catastrophic level of damage he surveyed could have been prevented.

Considerable effort has gone into providing additional “hard” storm surge protection for the New Orleans area since Katrina. The most recent effort is a $14 billion dollar project to upgrade the city’s levee system. Concerns have been raised that this system is already sinking, as is much of the city, and is insufficient to provide protection for any length of time.

Three additional recent large-scale hard seawall and gate projects were authorized in 2006 and undertaken by the Army Corp to enhance storm surge protection, which in this city can include flooding in from the Mississippi River and through Lake Pontchartrain. The Inner Harbor Navigation Canal Lake Borgne Surge Barrier was completed in 2013 at a cost of $1.1 billion. The Seabrook Floodgate was completed in 2012 at a cost of $165 million. The Gulf Intracoastal Waterway West Closure Complex was completed in 2014 at a cost of $1 billion.

A series of much smaller “soft” or resilience projects has also been planned. The “Living with Water in New Orleans” program, involves small scale demonstration projects to increase stormwater infiltration through permeable paving that would reduce land subsidence, and a park to enhance both water retention and recreation. Initial funding is $141 million dollars. A more comprehensive resilience plan, at a cost of $6.2 billion, has also been proposed. In addition, FEMA has provide funds to raise a small number of houses by enhancing foundations.

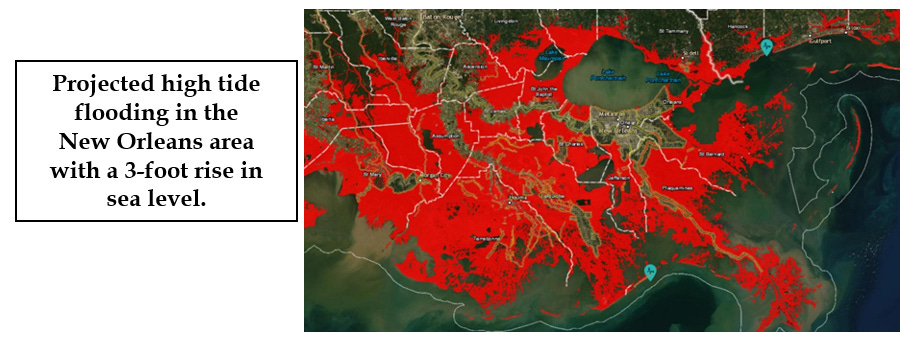

Projections for the impacts of predicted sea level rise make clear the challenge that New Orleans faces. One interactive site projects that a 5 foot rise in sea level, somewhat above the average projected for the end of the century, would leave 88% of New Orleans and most of the surrounding area, including Lake Pontchartrain under water. The interactive NOAA site mentioned above presents this image for normal high tide flooding with a 3 foot rise in sea levels.

The 2023 version of the state’s Coastal Master Plan focuses primarily on data updates, model improvements and outreach.

Sources:

General

NOAA’s interactive maps of impact of sea level rise are here: https://coast.noaa.gov/slr/

Here is another site with a slightly different approach

The Climate Central site is here:

https://coastal.climatecentral.org/

Projected sea level rise information is from the most recent (2021) science report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change:

https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/

Data on per capita spending on flood control is from:

https://www.nola.com/news/environment/article_a8c86a5c-3e65-5e0e-a7ad-7cc048263515.html

The GAO report on costs of storm damage is here:

https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-633r

An excellent overview of cities at risk and the Dutch Dialogues is here:

A link to the private company engaged in this process is:

https://wbae.com/living-with-water-2/

Media sources citing cities most at risk from sea level rise include:

New England

An overview of flood barriers in New England including links to the New Bedford, Providence and Stamford projects is here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flood_barrier

and information on the individual projects is from:

https://www.nae.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Flood-Risk-Management/Massachusetts/New-Bedford/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fox_Point_Hurricane_Barrier

Potential impacts and plans for the Boston area are here:

https://www.mass.gov/service-details/massachusetts-sea-level-rise-and-coastal-flooding-viewer

https://www.boston.gov/environment-and-energy/resilient-boston-harbor

New York

The impact of Hurricane Sandy is summarized here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hurricane_Sandy

Discussions of the Harbor Storm-Surge Barrier is here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_Harbor_Storm-Surge_Barrier

One visualization of the impact of sea level rise is here:

https://earth.org/data_visualization/sea-level-rise-by-the-end-of-the-century-new-york-city/

The East Side Coastal Resilience Project is described here:

https://www1.nyc.gov/site/escr/index.page

The plan for lower Manhattan is reported here:

A more general report on resiliency efforts is here:

Virginia Beach/Hampton/Norfolk

A report on the Dutch Dialogues process is here:

https://wetlandswatch.org/dutch-dialogues

A report on the actual meetings is here:

https://orf.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=5887c8fa1c754366bed999eb0c9b9f8a

Redirection of the planning for flood resilience in Norfolk following a Dutch Dialogue event in 2015 is included here:

An article on recent funding increases is here:

https://www.norfolk.gov/CivicAlerts.aspx?AID=6011

Charleston

The 2015 report is here:

https://charleston-sc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/10089/12_21_15_Sea-Level-Strategy_v2_reduce?bidId=

A description of the Dutch Dialogue process is here:

https://www.charleston-sc.gov/1974/Dutch-Dialogues

and the final report is here:

Recent Dutch Dialogue meeting reported here:

and time and cost estimates are from:

https://coast.noaa.gov/states/stories/charleston-sea-level-rise-strategy.html

A recent report on the raising of homes to avoid flooding damage is here:

The Image is from:

https://www.charleston-sc.gov/1193/Low-Battery-Seawall-Repair

Miami

The image of South Florida is from:

https://www.npca.org/case-studies/rising-sea-levels

Estimates of population displacement, sewage treatment plant isolation, and roads in the current 100 year flood zone are from:

https://e360.yale.edu/features/as-miami-keeps-building-rising-seas-deepen-its-social-divide

The 2070 street flooding estimate is here, along with a more dramatic image of the future:

The most recent Miami/Dade County sea level strategy document is here:

https://miami-dade-county-sea-level-rise-strategy-draft-mdc.hub.arcgis.com/

and a first annual update can be found using the Year One Progress Update link – the URL itself is too long to include here.

Houston

The main website for the Coastal Texas Study is here:

https://coastal-texas-hub-usace-swg.hub.arcgis.com/

The Executive Summary from the Army Corp of Engineers is here:

https://www.swg.usace.army.mil/Portals/26/Coastal%20TX%20Executive%20Summary_FINAL_20210827.pdf

Another complete description of the current proposed plan and how it has been changed in response to public input is here:

An interactive map of areas that will be protected from a 100 year flood by this project is here:

Additional stories on the impacts of Hurricane Ike and the political and planning aftermath include:

https://www.wired.com/story/a-dollar26-billion-plan-to-save-the-houston-area-from-rising-seas/

https://www.galvnews.com/news/image_2b5e02cb-b3ab-57a7-bffe-5b7fed3cf04e.html

New Orleans

Books on New Orleans, Katrina and what has happened since include:

Horowitz, Andy. 2020. Katrina: A History, 1915–2015. Harvard University Press

Brinkley, Douglas. 2007. The Great Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Harper Perennial

Background on tropical storm flooding history is here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Orleans#Threat_from_tropical_cyclones

An overview of the levee system and Living With Water projects is included here:

Information on the Lake Borgne, Seabrook and Intracoastal Waterway projects can be found here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IHNC_Lake_Borgne_Surge_Barrier

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seabrook_Floodgate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulf_Intracoastal_Waterway_West_Closure_Complex

Information on the current Living With Water program is here:

https://csengineermag.com/living-with-water-in-new-orleans/

The more complete plan is outlined here:

https://gnoinc.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/01/GNOH2O_Pamphlet_Trimmed_FINAL.pdf

Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan site is here:

https://coastal.la.gov/

The interactive map site projecting 88% flooding with a 5 foot sea rise is here:

https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2012/11/24/opinion/sunday/what-could-disappear.html

NOAA’s interactive maps of impact of sea level rise are here: https://coast.noaa.gov/slr/