The Massive Sargassum Blob - Coming Soon to a Beach Near You!

Is this the biggest shift in global biology in the last 12 years?

We have weathered another Polar Vortex breakdown, record-breaking Atmospheric Rivers, and Zombie Ice, and just when you thought it was safe to go back into the water, here comes the Massive Sargassum Blob from the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt.

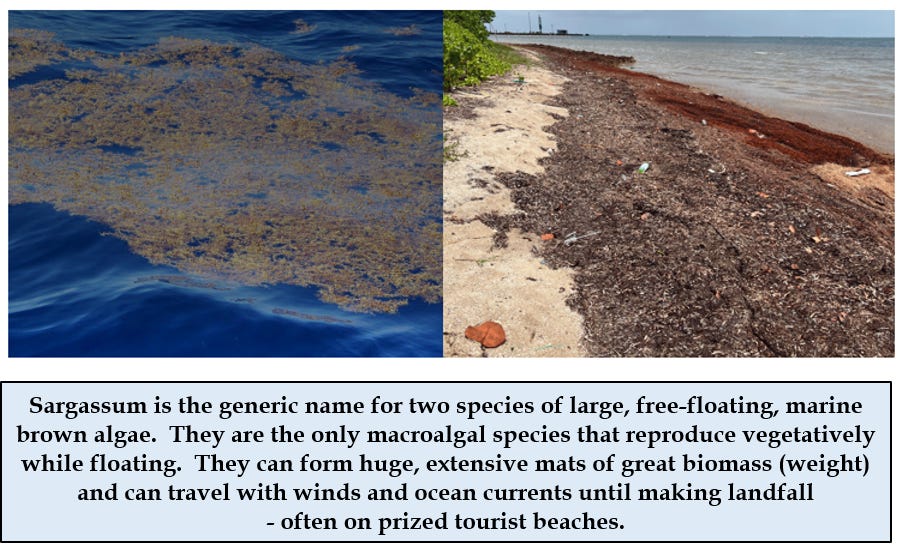

Well, the headlines aren't quite like that, but there has been quite a bit in the news lately about a massive seaweed bloom in the tropical Atlantic in an area now called The Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. Beach communities around the Caribbean and up the Florida coast are bracing for a major landfall of the brown macroalgae known by the generic name of Sargassum.

Is this really such a new and newsworthy phenomenon? Landfall of macroalgae on beaches has always happened, but the stories seem to predict a major uptick in these invasive mats.

Yes Indeed. Huge Sargassum blooms now occur routinely in parts of the tropical North Atlantic where none were seen before. On land, this would be equivalent to converting dry desert to forest.

How do we know this?

In 2011, researchers at The Optical Ocean Laboratory at the University of South Florida began using images from four remote sensing satellites to map the distribution of Sargassum blooms and predict where the mats might make landfall. They developed both a Floating Algal Index (Sargassum mass) and a Color Index (showing currents and eddies) to make these predictions.

Their images document the dramatic increase in these algae over just the last 12 years - and so the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt was born.

If this really is a new phenomenon, how did it happen?

If you are a fan of adventure stories from the age of sail, the Sargasso Sea may conjure an image of a vast, exotic, tropical seascape of calm seas and clear waters, but for sailors, that same calm brought the threat of being trapped for days on end without wind to fill their sails.

The Sea itself is a vast, irregular, shifting oval of open ocean in the North Atlantic formed, or trapped if you will, by the North Atlantic Gyre. Gyres are very large circulation patterns that exist in every major ocean, and the North Atlantic Gyre is framed by the four named currents in this image. One NOAA site describes the Sargasso as a unique ecosystem; the only Sea bounded only by currents (not continents) and the only one hosting the massive macroalgal mats that support many rare and commercially important species.

The calm, clear water at the center of a Gyre may be beautiful, but that clarity results in part from very low nutrient levels leading to very low rates of algal growth. The term "biological desert" has been applied to these clear waters.

But the southern edge of this Gyre has recently gone from near desert to algal forest. What could cause such a dramatic shift?

A NOAA website describing the increase offers a first hypothesis - that a major change in wind patterns in 2009-2010 drove some Sargassum from its usual range in the western Atlantic toward Europe. There it met the Canary Current which drove it further south and into the North Atlantic Equatorial Current that now carries the bloom back towards the Americas. Conditions appear to have been optimal for the growth of Sargassum in this new environment.

While the trend of increasing Sargassum biomass is clear, there is some significant year-to-year variability.

Some reports link that variability to the outflow of major rivers feeding this ocean region, such as the Amazon and the Orinoco, and suggest that variation in nutrient loads from these rivers could drive changes in Sargassum mass. Perhaps they also contributed to that optimal environment for growth. Eutrophication (excess nutrient loading, algal growth and oxygen depletion through decomposition) has occurred on a massive scale in the "Dead Zone" at the mouth of the Mississippi River, so yes, river nutrient loads can affect biological processes in marine environments on this massive scale.

Another site suggests variation in the amount of wind-blown dust from the Sahara Desert might be important. A previous essay in this series showed how both hurricanes and Amazon forest health can be affected by Saharan dust storms, so why not Sargassum?

And what are the consequences of this apparently massive change in marine biology in the North Atlantic - is this a good thing or a bad thing? This Substack site does not go into politics and policy, and, as "good" and "bad" are, like beauty, in the eyes of the beholder, we won't make that judgement call. However, we can describe some of the environmental outcomes of an expanding Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt as seen from two very different points of view.

To the tourist industries around the Caribbean and up the Florida coast, there is little good in the massive piles of rotting brown algae that can accumulate on their beaches. Popular tourist destinations can become nearly unusable just because of the huge accumulations of Sargassum, and even more so from the odor emitted as the algae decay. Disruption of fishing and boating can also occur. Economic losses can be considerable, as they were during the red tide outbreak in Florida in the 2010s.

On the other hand, it is intriguing that the initiation of this Sargassum outbreak (around 2011) coincides with the formation of the Sargasso Sea Commission, whose goal is the conservation and care of that Sea, and whose website offers a very different description of those algal mats.

"The Sargasso Sea is...a place of great beauty and ecological value, a golden floating forest in the surface waters of the North Atlantic – an oasis of marine life and the only sea without shores—containing species that are endemic to Sargassum and many others that are specially adapted for life amongst the floating canopy."

According to the Commission, floating Sargassum supports a unique biological community that has evolved to include a long list of endemic species (those that occur nowhere else). Endemics include 10 species of crabs, and the uniquely camouflaged Sargassum Angler Fish. Overall, 145 species of invertebrates and 127 species of fish have been found associated with floating Sargassum mats. The prospects of those endemic species must have improved markedly over the last decade.

To the members of the Sargasso Sea Commission, a thriving and growing population of Sargassum mats is a good thing for biodiversity and productivity. A NOAA site on the Sargasso Sea makes the case that the productivity of these mats support not just the species within them, but also populations of commercially important species harvested in this marine region.

There is a third perspective that relates more directly to the focus of this Substack site. Was this major change caused by a changing climate system, or might there be feedbacks from this change to the climate system.

If the redistribution of Sargassum did indeed result from truly unusual, possibly never-before-seen wind patterns, then the entire phenomenon could have a climate change origin. To the extent that nutrient runoff from major rivers fuels Sargassum growth, then human actions can increase the extent and mass of the mats.

On the other hand, one site says that Sargassum grows best in relatively cool waters, so continued warming of the tropical Atlantic might cap Sargassum growth.

Some important questions still need definitive answers.

And a final possible connection relates to the global carbon cycle.

Sargassum blooms contain a massive amount of carbon. At least one site suggests that this could be an important removal from the atmosphere and the global carbon cycle if much of this biomass sinks (rather than ending up on beaches). Growing and sinking algal carbon has been a goal of geoengineering proposals for decades.

Sadly, while the amount of carbon in Sargassum (perhaps 10 million tons at any one time) is huge compared to most values for the open oceans, it pales in comparison with the nearly 40 billion tons of annual carbon dioxide emissions from the burning of fossil fuels. It is also unclear how much of that biomass actually sinks, as opposed to landing on beaches. One new company has developed automated pods to trap Sargassum and transport it down into the deep ocean, but this technology is proposed first as a way to reduce landfall, with carbon removal as a possible secondary benefit.

Regardless of your point of view, it seems clear that a major new marine ecosystem has been formed (or an existing one has been greatly expanded). Such a rapid change bears careful watching as we track human influences on climate and the global environment.

Just what is the future of the Massive Sargassum Blob and the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt?

Sources

The images of floating and beached Sargassum are from:

https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/massive-bloom-of-seaweed-in-tropical-atlantic/https://response.restoration.noaa.gov/orr-supporting-response-sargassum-st-croix-us-virgin-islands

Much more dramatic images can be found online!

Some basic information on the Sargasso Sea can be found here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sargasso_Sea

The University of South Florida (USF) Optical Oceanography Laboratory site is:

https://optics.marine.usf.edu/projects/saws.html

and the images of Sargassum distribution are from:

https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/151188/a-massive-seaweed-bloom-in-the-atlantic

The USF website includes images from 2019-2022 which also show extensive Sargassum distribution.

The image of the currents surrounding the Sargasso Sea was modified from one produced by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that can be found here:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sargasso.png

The concept of Gyres as "biological deserts" is described here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ocean_gyre

NOAA websites relating to Sargassum include:

https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/sargassosea.html

https://www.aoml.noaa.gov/tracking-sargassum/

and

https://cwcgom.aoml.noaa.gov/cgom/OceanViewer/

which includes current estimates of Sargassum distribution

A history of the expansion of Sargassum distribution and possible causes can be found here:

https://coastwatch.noaa.gov/cwn/news/2023-04-04/sargassum-faq.html

NASA websites relating to Sargassum include:

https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/151188/a-massive-seaweed-bloom-in-the-atlantic

The Sargasso Sea Commission website is:

http://www.sargassoseacommission.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=106

And a history of the Commission is here:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2021.668253/full

The 3-D image of the Sargasso Sea environment is from:

https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/sargassosea.html

Data on the size of the Mississippi delta Dead Zone can be found here:

https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/larger-than-average-gulf-of-mexico-dead-zone-measured

Two reports on the role of Saharan dust in feeding Sargassum blooms are:

https://earthsky.org/earth/iron-from-the-sahara-helps-fertilize-atlantic-ocean/

https://www.nature.com/articles/nature13482

Efforts to use or sink Sargassum carbon include:

https://algaeplanet.com/seaweed-generation-developing-technology-to-sink-sargassum/